Low's Pitcher Plant: the 'Toilet Pitcher'Nepenthes lowii Hook.f.

| Low's Pitcher Plant in Borneo, with droppings visible in the mouth. Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris, 2005. |

Introduction

Nepenthes lowii is a pitcher plant, a group of carnivorous plants, that is found in Malaysian Borneo. While pitcher plants are more famous for being deadly pitfall traps that drown insects, Low's Pitcher Plant is different from the others because| Upper pitcher of Nepenthes lowii in their natural habitat. Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris 2005. |

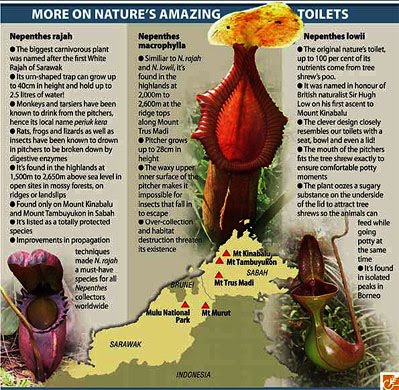

The other two species of pitcher plant showing similar adaptation are N. macrophylla and N. rajah[1] [2] . For more on the weird 'behavior' of this plant and the treeshrew, the pitcher plant's habitat and best growing conditions, and to find out what other species it is closely related to, read on.

Discovery and naming

The plant first became known to westerners when Sir Hugh Low, a British administrator and naturalist, discovered it the first documented ascent of Mount Kinabalu in 1851. He wrote:"9th March.- At 7 1/2 A.M. we left our rocky camp, and immediately began a steep ascent. [...] A little way further we came upon a most extraordinary Nepenthes, of, I believe, a hitherto unknown form, the mouth being oval and large, the neck exceedingly contracted so as to appear funnel shaped, and at right angles to the body of the pitcher, which was large, swollen out laterally, flattened above and sustained in a horizontal position by the strong prolongation of the midrib of the plant as in other species. It is a very strong growing kind and absolutely covered with its interesting pitchers, each of which contains little less than a pint of water and all of them were full to the brim, so admirably were they sustained by the supporting petiole. The plants were generally upwards of 40 ft long, but I could find no young ones nor any flowers, not even traces of either."

(Low, 1852)[3]

A few years later in 1859, the famed botanist Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker formally described the species, and named it after its discoverer[4] .

Table of Contents

Quick Facts

| Group |

Pitcher Plants |

| Classification |

Angiosperms |

| Eudicots |

|

| Core Eudicots |

|

| Caryophyllales |

|

| Nepenthaceae |

|

| Nepenthes |

|

| Conservation Status |

Vulnerable D2* (IUCN, 2013) |

| Distribution |

Select mountains in northern Borneo (see distribution map) |

| Habitat |

Mossy ridges over a range of soil types; on trees in upper montane, limestone, ultra basic and heath forests. |

| Altitude |

1500-2600m |

| Growth Habit |

Liana; Rosette |

| Duration |

Perennial |

| Cultivation |

Easy-Medium |

General Information on Nepenthes Pitcher Plants

Pitcher plants are those carnivorous plants which posses a leaf modified into a jug (pitcher) or more-or-less funnel-like ('infundibuliform') shape, in order to catch animals (mainly insects). This is done in order to supplement the nitrogen (N) intake of the plants, which are usually not met by their 'poor' (N-deficient) substrate[5] . The two main groups of pitcher plants are the Nepenthaceae and Sarraceniaceae (Sarracens). While the latter is restricted to the Americas, Nepenthaceae are distributed around the Indian Ocean, in the single group Nepenthes; scientists in Germany used plastid DNA and

|

| Global distribution of Nepenthes. Note presence in Madagascar and the Seychelles. From Wikimedia Commons under 'Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported' Licence. |

|

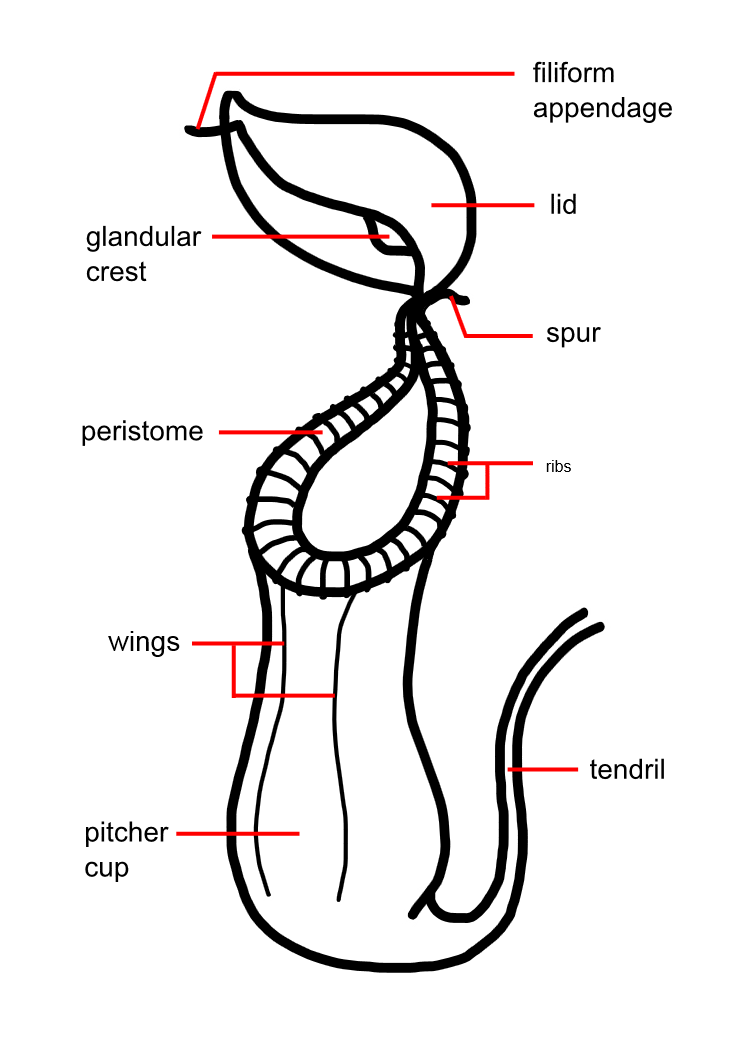

| General features of the upper pitcher type of 'Monkey Cups'. By Mgiganteus1 (2008), Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic licence. |

Pitchers vary widely in colour, shape, and size; they may be between 5 to 45cm in length in Nepenthes species, and up to a meter tall in the White Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia leucophylla)! While Sarracens develop pitchers directly from a rosette on the ground, Nepenthes show a more complex morphology and development. The Nepenthes pitcher originates at the tendril, which is the elongated midrib of the leaf; this terminates as a small spur, the tip of the leaf, behind the lid (see diagram). Where the tendril is attached to the pitcher is different between upper (or aerial) and lower (or terrestrial) pitchers, attaching from behind in the latter and in front in the former.

The 'wings' of the pitchers, especially in those species where the trap rests on a solid surface/another plant, may serve as guiding lines or 'run way lights', tempting crawling insects and arachnids to climb up to the mouth of the pitcher, using scent glands. Only in the lid can any nectar be obtained, but this is usually also the point most directly overhanging the pitcher mouth and so the most likely to

Many of the animals which visit pitcher plants are not actually caught [7] [8] , especially in dry conditions [9] , and the provision of sugars in nectar, which cost the plant relatively little [10] , provide valuable energy for the many individuals that visit and are not caught, thus potentially benefiting the prey species at the population level [11]

In this video, we see how the slippery walls of the pitcher prevent an unknown dipteran species ('horsefly') from climbing out of the trap, and how the constricted walls prevents, in the case of this large insect, escape by flight.

Scientific and General descriptions

|

| An upper pitcher of Nepenthes lowii showing distinctive constricted middle and gaping mouth. Taken on Mt. Murud, Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris (2007). |

The original description by J.D. Hooker (1859)[12] reads as follows:

"NEPENTHES LOWII, H. f. Caule robusto tereti, foliis crasse coriaceis longe crasse petiolatis lineari-oblongis, ascidiis magnis curvis basi ventricosis medio valde constrictis, ore maximo ampliato, annulo 0, operculo oblongo intus dense longe setoso. [...]

Hab. Kina Balou, alt. 6000-8000 feet (Low).

A noble species with very remarkable pitchers, quite unlike those of any other species. They are curved, 4-10 inches long, swollen at the base, then much constricted, and suddenly dilating to a broad, wide, open mouth with glossy shelving inner walls, and a minute row of low tubercles round the circumference ; they are of a bright pea-green, mottled inside with purple. The leaves closely resemble those of Edwardsiana and Boschiam in size, form, and texture, but are more linear-oblong. [...] The male raceme is 8 inches long, dense-flowered. Peduncles simple. Perianth with depressed glands on the inner surface, externally rufous and pubescent. Column long and slender. Female inflorescence : a very dense oblong panicle ; rachis, peduncles, perianth, and fruit covered with rusty tomentum. Capsules 2/3 inch long, 1/6 broad."

| Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris 2005 |

Distribution

(see also: Phylogeography)

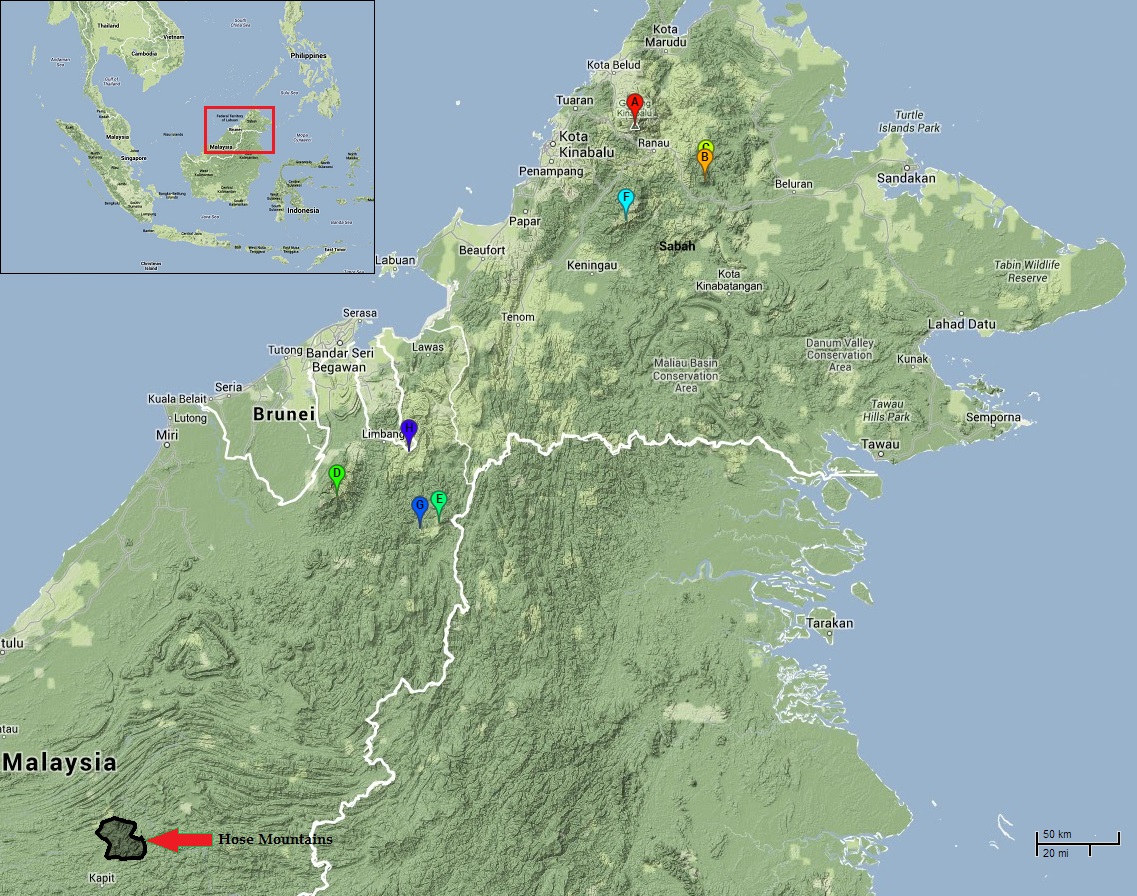

Low's Pitcher is endemic to Malaysian Borneo: it is found only in Sabah and eastern Sarawak. A highland species, it is found on a handful of highlands and isolated peaks, anywhere between 1,500m and 2,600m [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] .

|

| Confirmed distribution of Low's Pitcher (Sabah and Northern Sarawak): A = Mt. Kinabalu; B = Mt. Mentapok; C = Mt. Monkobo; D = Mt. Mulud; E = Mt. Murud; F = Mt. Trus Madi; G = Mt. Batu Lawi; H (dark purple) = Mt. Pagon. Unconfirmed population in Hose Mountain Range (shaded) (see text). Made using Google Maps (various sources). |

In Sabah it occurs on Mount Kinabalu, Mt. Trus Madi, Mt Mentapok and Mt. Monkobo (with single reports of occurrences on Mt. Alab and Mt. Tambuyukon, not shown on map).

In north Sarawak it can be found Mt. (Bukit) Pagon, Mt. Mulu, Mt. Murud and Mt. (Bukit) Batu Lawi. There are several other reports of occurrences within this area, though as each mountain did not occur more than once in the literature so far published, they were excluded.

While these two northerly clusters are well established, the cluster on and around the Hose Mountains (Pegunungan Hose) is less well so. According to Ch'ien Lee, a specimen identified as N. lowii, collected from Mount Temedu in the northern end of the range (but which "clearly showed differences from this species" (in pitcher morphology), was deposited in the Sarawak Herbarium in March 1964; however, Lee failed to find any individuals of this species during his expedition[19] . In a review on the distribution of Bornean Nepenthes species, Adam et al. list N. lowii as having being collected from Mt. Temedu: as no source is listed, it is not clear if this is referring to the hebarium specimen found by Lee [20] . Within the region but southeast of the Hose Mountains, Danser (1928) mentions a record of Low's Pitcher from Bukit (Mount) Batu Tiban, seen but not collected by Eric Mjöberg in 1926 [21] . Therefore the occurrence of this species south of Bukit Batu Lawi, in northern Sarawak, seems uncertain at best.

Best of Three Toilets

Mutualism with Tupaia Tree Shrews

In this video, we see extremely rare (and unique among published materials/videos) an example of the way Low's Pitcher plant interacts with the Mountain Treeshrew, Tupaia montana, by providing it with sweet nectar from its lid, in order to benefit from the shrew's droppings.

(If the video doesn't play, an mpg file of the same should be downloadable via this link: Tree shrew feeds from //N. lowii//. Video courtesy of the Royal Publishing Society; included within the online supplementary materials for Clarke et al., 2009[22] ).

Pitcher Morphology and 'Trapping' Mechanism

|

| Upper pitcher of N. lowii, showing its important adaptations to capturing droppings of the Mountain Tree Shrew. Photo credit: Jeremiah Harris. |

The morphology of N. lowii makes it so distinct as to be almost impossible to confuse with other species[23] [24] . It is this distinctive morphology which allows it to so effectively 'trap' its main (nitrogen) resource, the faeces of Tupaia montana [25] [26] . Among its adaptations to capturing faecal matter are its wide and elongated mouth opening, a concave, elongated and near-upright lid, which provides a sweet nectar to attract the Mountain Treeshrew, and a reinforced 'woody' pitcher and tendril, helping to support the weight of the mutualistic mammal [27] [28] [29] . Perhaps the most significant difference from the 'standard' Nepenthes pitcher is the near loss of the peristome (rim) in the upper pitchers.

|

| Droppings of the Mountain Tree Shrew in N. lowii. Photo credit: Michael Lo, 2012. |

This rim is one of the most important trapping mechanisms in other Nepenthes species which derive their N requirements from captured insects (mainly spiders and ants): when wet, the peristome becomes extremely slippery to the arthropods crawling on it in order to reach the nectar near the base of the lid, and they 'aquaplane' or slide on a film of water of the peristome, having no grip whatsoever, and fall into the pitcher mouth [30] [31] [32] . While water lubrication prevents attachment by the soft adhesive pad of (weaver) ants, the anisotropic surface topography of the regular peristome also prevents the claws of the tarsus from finding purchase on the rim, and thus total friction between the insect and inwardly-curved peristome is reduced to effectively zero. However, Low's Pitcher does not require this feature, obtaining nutrients in its upper pitcher primarily from faeces (and leaves, when older and less visited by tree shrews), and so we can hypothesise that the cost of this feature (the peristome) selected against its development when not needed (Low's Pitcher has also lost the microstructure of epicuticular wax which lines the inner surface of most Nepenthes species, making it impossible for arthropods to crawl out by presenting a flaking, powdery surface [33] [34] ). Possibly the stronger selection pressure was a surface which T. montana (the tree shrew) could comfortably grip and rest on.

But back to Low's Pitcher!

The lid of N. lowii exudes a sweet nectar on its lid, providing sugars for the Mountain Tree Shrew. The distance from this lid to the back of the mouth of the pitcher correlates quite well with the average length of T. montana,

|

| The sweet, nectar-like secretions that are excreted by special glands on the lid, will often build up in a visible white layer in cultivation, due to there being no shrews to lick it up! Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris, 2013. |

Systematics

Summary

A summary of the classification of this species is given. Ranks above species are left out due their controversial nature among some systematists.

| Classification |

Angiosperms |

| Eudicots |

|

| Core Eudicots |

|

| Caryophyllales |

|

| Nepenthaceae |

|

| Nepenthes |

|

| Species |

Nepenthes lowii |

Taxonomy

Due to its distinctive pitcher morphology, N. lowii is generally regarded as being difficult to confuse with other species (e.g. [37] [38] ). The nearest apparent match to the species is the closely related N. ephippiata Danser (ephippium = saddle); the lower pitchers are similar, but the upper pitchers differ in in that only N. lowii possesses the 'wasp waist' or constricted middle section, a much longer spur, and the lid of N. ephippiata is proportionally much larger and more concave than that of N. lowii. The petiole of the 'Saddle-Leaved pitcher' is also highly distinctive, so much so that when it was originally described Danser did not have a pitcher to work from, using only the petiole of the photosynthetic leaf!

There are two keys given for the Nepenthes species of Borneo, where N. lowii is endemic. They given here as an indication of the characteristic distinguishing this species from others in Nepenthes. The direct line of questions found in the mainly dichotomous key of Clarke [39] (including both options in the final question) is as follows:

1. Plant characters not matching all of those listed [key immediately eliminated N. mollis] -> 2. Peristome ribs not coarse, always less than 4mm apart -> 5. No large thorns under pitcher lid -> 6. Insertion of tendril not significantly distant from leaf apex -> 8. Fringe hairs never present on upper margin of pitcher lid -> 10. Lower surface of lid of upper pitchers either glabrous or with a dense covering of bristles, but without a glandualr crest, boss or appendages -> 17. Pitchers with many conspicuous bristles on lower surface of lid ->

18. Lid bristles short, thick and blunt-tipped, pitcher lid larger than the mouth in upper pitchers. Upper pitchers only slightly narrowed beneath the uppermost part: N. ephippiata.

Lid bristles hair-like, fine and tapered, pitcher lid smaller than the mouth in upper pitchers. Upper pitcher highly constricted beneath the uppermost point: N. lowii.

Jebb & Cheek's key [40] , in the same format, is as follows:

1b. Pitcher without a white ring of hairs below the peristome -> 2b. Peristome not so; lid orbicular, or narrower than long -> 3b. Lid less than 3 times as long as wide; with glands -> 4a. Underside of lid with long bristles or thick tubercles to several mm in length ->

5a. Lid bristles fine, tapering; peristome ribs of upper pitchers scarcely developed: N. lowii.

b. Lif bristles thick (1 mm), blunt-tipped; peristome ribs always apparent: N. ephippiata.

| N. lowii x truncata. Permission and (c) Jeremiah Harris, 2013. |

|

Comparison of Low's pitcher and its closest relative, the the Saddle-Leaved pitcher, Nepenthes ephippiata. Note the differences in relative lid size, peristome presence in N. ephippiata, 'wasp waist' of N. lowii, and vertical 'stomach' of N. lowii. |

|

| N. lowii (upper pitcher). Photo credit: Andreas Wistuba (permission pending) |

N. ephippiata (upper pitcher). Photo credit: Andreas Wistuba (permission pending) |

NATURAL HYBRIDS

"Natural hybrids can be possible. However, hybrid offspring rarely succeeds to develop into a wild population [41] "Low's Pitcher is known to naturally cross with (in this case, one generation is confirmed to interbreed; there is no evidence of these being fertile with the parent populations) with N. fusca, N. macrophylla (N. × trusmadiensis)

, and N. stenophylla. This ability gives growers a chance to produce many unusual shapes and varieties, which may not occur in the wild, such as N. lowii x truncata pictured, which shows both a mixture or characters of both parent species, and intermediate characters.

Phylogeny and Phylogeography

Nepenthaceae is a mono-generic 'family', containing the 82-91 species of Nepenthes [42] [43] (see Clarke, 1997 [1] for a partial discussion of the taxonomic issues surrounding Nepenethes).

(Ellison & Gotelli, 2009). Nepenthaceae is within the Caryophyllales of the Core Eudicots; carnivory, and indeed pitchers, have arisen more than once among the angiosperms, in the Asterids (e.g. Pinguicula, Sarracenia) and the Rosids (Cephalotus) within the Eudicots, and in Bromeliacea (e.g. Brocchinia spp.) within the Monocots.

Originally Danser defined several sub-generic divisions among Nepenthes, and did not acknowledge any subspecies or other infraspecific taxa; the former construct was found to be artificial and fell out of favour, while the latter convention is more recently being overturned (e.g. naming of subspecies by some taxonomists [44] ).

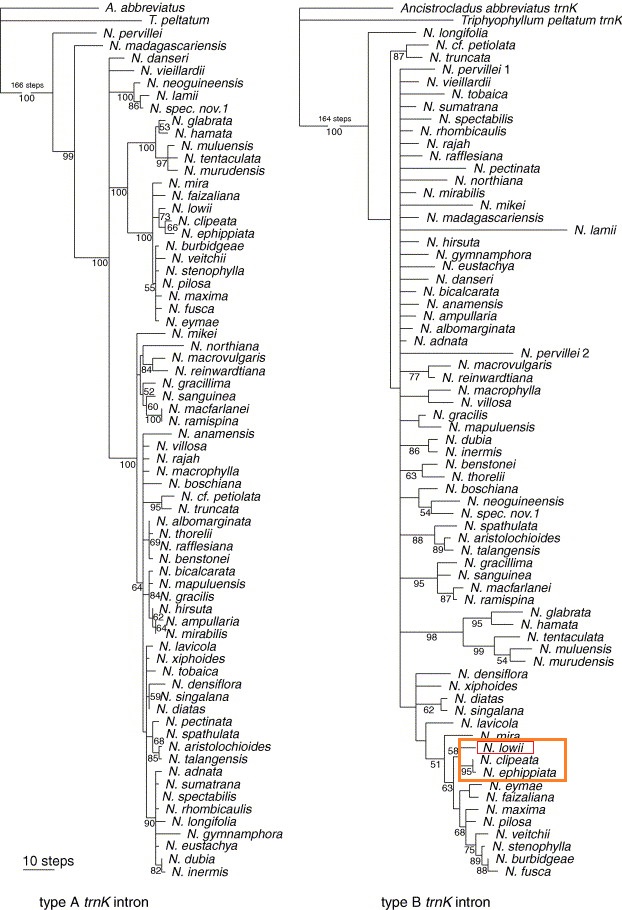

Recent molecular studies have found N. lowii to be in a clade with N. ephippiata and N. clipeata [45] , with further studies indicating that N. ephippiata is most closely related to N. clipeata, with N. lowii as sister species to this clade [46] [47] . These studies also found that N. rajah and N. macrophylla are not closely related to this clade within Nepenthes (important due to the convergent nature of their strategy of N acquirement), being placed within separate, genetically-defined clades by Meimburg and Heuble, base on a strict consensus of shortest trees using trnK intron data [48] . It was also found that use of peptide transferase 1 (PTR1) produced groups within Nepenthes (on a strict consensus tree of shortest trees) that largely agree with those produced by using trnK intron. [more info to come]

The position of Nepenthes/Nepenthaceae within the Carophyllales is not so well constrained, with many different trees of the major groups within Carophyllales being given by different authors [49] . Of particular significance is the position of Nepenthaceae in relation to Droseraceae, its long-hypothesised sister taxon based on morphological evidence, in particular the presence and mechanisms of carnivory; this result is not always found by genetic studies. Meimburg et al. present Nepenthaceae and Droseracea as members of a single, relatively well-supported clade, but not as sister taxa [50] . [more info to come]

Far-flung origins

While most pitcher plants posses pitchers and leaves that are too soft to be readily fossilised, and as such the fossil record for Nepenthes is poor. Fortunately, fossil evidence of Nepenthes can be found in their well-preserved and highly differentiated pollen grains, allowing association with living species or their ancestors to a high degree of certainty [51] . Pollen evidence has been found for a Bornean distribution matching that of the present day going back to the Miocene [52] . However far older Nepenthes pollen has been found from deposits in Europe, from the Eocene period [53] as read in [54] .

[more info to come]

Apendices

Appendix 1.

Definition of Vulnerable species (and categories applying to N. lowii), as given by the IUCN:

"VULNERABLE (VU)

A taxon is Vulnerable when it is not Critically Endangered or Endangered but is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future, as defined by any of the following criteria (A to E):

[...]

D) Population very small or restricted in the form of either of the following:

1) [...]

2) Population is characterised by an acute restriction in its area of occupancy (typically less than 100 km2) or in the number of locations (typically less than five). Such a taxon would thus be prone to the effects of human activities (or stochastic events whose impact is increased by human activities) within a very short period of time in an unforeseeable future, and is thus capable of becoming Critically Endangered or even Extinct in a very short period."

References

Clarke, C, 1997. Nepenthes of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Koto Kinabalu.

Low, H, 1852. Notes on an ascent of the mountain Kina-balow. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and eastern Asia6, 1-17.

Hooker, JD, 1859. XXXV. On the origin and development of the pitchers of Nepenthes, with an account of some new Bornean plants of that genus.The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London22, 415–424.

Moran, JA, Clarke, CM, 2010. The carnivorous syndrome in Nepenthes pitcher plants.Plant Signaling & Behavior 5, 644-648.

Meimberg, H, Wistuba, A, Dittrich, P, Heubl, G, 2001. Molecular Phylogeny of Nepenthaceae Based on Cladistic Analysis of Plastid trnK Intron Sequence Data. Plant Biology 3, 164-175.

Moran, JA, 1996. Pitcher Dimorphism, Prey Composition and the Mechanisms of Prey Attraction in the Pitcher Plant Nepenthes Rafflesiana in Borneo. Journal of Ecology 84, 515-525.

Hooker, JD, 1859. XXXV. On the origin and development of the pitchers of Nepenthes, with an account of some new Bornean plants of that genus. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 22, 415–424.

Danser, BH, 1928. The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies. Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, Série III, 9, 249-438.

Lee, C, 2002. //Nepenthes// species of the Hose Mountains in Sarawak, Borneo. Proceedings of the 4th International Carnivorous Plant Conference, Tokyo. The International Carnivorous Plant Society, Tokyo.

Clarke, CM, Bauer, U, Lee, CC, Tuen, AA, Rembold, K, Moran, JA, 2009. Tree shrew lavatories: a novel nitrogen sequestration strategy in a tropical pitcher plant. Biology Letters 5, 632-635.

Clarke, C, 1997. Nepenthes of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Koto Kinabalu.

Phillipps, A, Lamb, A, Lee, CC, 2008. Pitcher Plants of Borneo. 2nd ed. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia.

Clarke, CM, Bauer, U, Lee, CC, Tuen, AA, Rembold, K, Moran, JA, 2009. Tree shrew lavatories: a novel nitrogen sequestration strategy in a tropical pitcher plant. Biology Letters5, 632-635.

Adam, J, 1997. Prey spectra of Bornean //Nepenthes// species (Nepenthaceae) in relation to their habitat. Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science 20, 121-134.

Chin, LJ, Moran, JA, Clarke, C, 2010. Trap geometry in three giant montane pitcher plant species from Borneo is a function of tree shrew body size. New Phytologist186, 461-470.

Clarke, C, 1997. Nepenthes of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Koto Kinabalu.

Clarke, C, 1997. Nepenthes of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Koto Kinabalu.

Jebb, M, Cheek, M, 1997. A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 42, 1-106.

Clarke, C, 2002. Guide to the Pitcher Plants of Peninsula Malaysia. Natural History Publications, Borneo.

Jebb, M, Cheek, M, 1997. A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 42, 1-106.

Adam, JH, Hamid, HA, 2006. Pitcher Plants (Nepenthes) Recorded from Keningau-Kimanis Road in Sabah, Malaysia.International Journal of Botany 2, 431-436.

Meimberg, H, Wistuba, A, Dittrich, P, Heubl, G, 2001. Molecular Phylogeny of Nepenthaceae Based on Cladistic Analysis of Plastid trnK Intron Sequence Data. Plant Biology 3, 164-175.

Meimburg, H, Heuble, G, 2008. Introduction of a Nuclear Marker for Phylogenetic Analysis of Nepenthaceae. Plant Biology 8, 831-840.

Meimburg, H, Heuble, G, 2008. Introduction of a Nuclear Marker for Phylogenetic Analysis of Nepenthaceae. Plant Biology 8, 831-840.

Meimberg, H, Diitrich, P, Bringmann, G, Schlauer, J, Heubl, G, 2000. Molecular Phylogeny of Caryophyllidae s.l. Based on MatK Sequences with Special Emphasis on Carnivorous Taxa. Plant Biology 2, 218-228.

McPherson, S, 2009. Pitcher Plants of the Old World Volume One. Redfern Natural History Productions, Dorset, England.